By Athayde Tonhasca

The Dutch painter Hiëronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516), the master of nightmarish landscapes and odd creatures, apparently had a thing for strawberries: the fruit is depicted thrice in his famed The Garden of Earthly Delights. The painting’s symbolism and the role of strawberries have been debated for a long time. The plant may be an allegory of sin and temptation, as it grows by creeping low on the ground, just like the Garden of Eden’s serpent. Strawberries were seen by some overimaginative medieval commentators as sensuous, erotic or virginal: Shakespeare’s Desdemona sported a handkerchief decorated with strawberries, a representation of fidelity. Others saw the fruit under a pious perspective, representing drops of Christ’s blood, while the plant’s tripartite leaves symbolised the Trinity. This religious angle explains the abundance of manuscripts, carvings, paintings and heraldic symbols decorated with strawberry fruits, leaves and flowers.

Strawberries have a rich history of cultural symbolism in Medieval Europe, but they are scarce in culinary references. The main reason for that was the organoleptic shortcomings of the species available then, namely the woodland (Fragaria vesca), musk (F. moschata) and green (F. viridis) strawberries. These wild strawberries can be tasty, but also tangy, acidic, bitter, small, easily bruised and damaged by insects and diseases. So they were not on people’s lists of most desired fruits. All that changed in the 1700s, when European horticulturalists crossed two imports from the Americas, the Chilean (F. chiloensis) and Virginia (F. virginiana) strawberries. The resulting hybrid, Fragaria x ananassa, is the garden strawberry known to us today, and the source of all modern varieties cultivated around the world.

The garden strawberry has an agreeable balance between sweetness and acidity, and a complex blend of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) gives the fruit its distinct aroma and flavour. Other appealing traits such a hardiness, uniform shape and large size helped make the garden strawberry one of the most popular fruits in the world, and not only as a table staple: natural or synthetic strawberry extracts made their way into hundreds of products, from ice cream to cakes, jam, jelly, hard sweets, alcoholic beverages, non-alcoholic beverages, chewing gum, pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. The demand for fresh and frozen strawberries has been growing steadily for many years, and is not abating: strawberries are grown commercially in 76 countries, generating significant income for local economies. So, naturally, strawberry pollination has enormous importance. However, some of the plant’s morphological aspects renders this process less than straightforward.

Strawberries, just like raspberries and blackberries, are aggregate fruits – or etaerios, if you want to be fancy – meaning that the succulent part we eat (the receptacle) develops from several ovaries fused together. In other words, each strawberry consists of one plump receptacle; the yellowish pips embedded on the strawberry’s surface, which are often assumed to be seeds, are in fact the fruits. Each one is an achene, a type of single-seeded, dry fruit. So, a strawberry is not a berry at all: berries are simple fruits, that is, they derive from one ovary that produces a single fleshy bit. A tomato is a berry, and so is a banana. Botany is complicated.

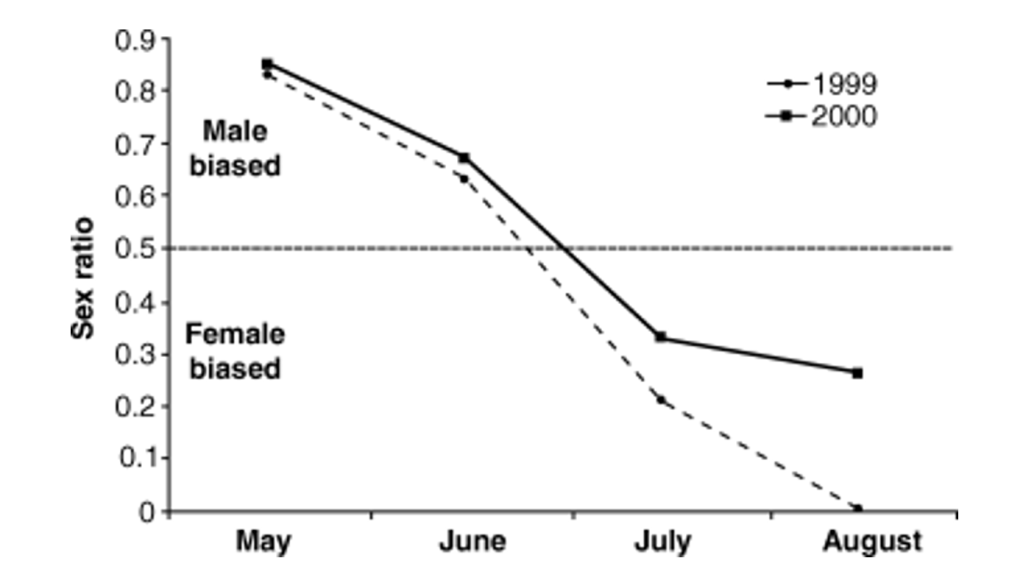

Strawberry flowers have male and female structures – they are hermaphroditic – and most varieties can self-pollinate: wind, rain and gravity take care of that. It may sound like the plant has its reproduction requirements sorted out, but that’s not so. The stigmas (the parts that receive the pollen) are usually ready before the anthers (the parts that produce the pollen), so that a plant may need to cross-pollinate with neighbours. But that’s the least of its difficulties.

A large strawberry fruit holds about 200 achenes, and each one of them contains an ovule. Most of them must be fertilised so that the tissue around the achenes develops fully to form the enlarged receptacle. Unfertilized ovules do not stimulate tissue growth, and if there are too many of them, the result is a misshapen strawberry. These malformed fruits are perfectly healthy and edible but have little commercial value.

The large number of ovules requiring pollination is a challenge because wind, rain and gravity take care of 60 to 70% of them. The rest must be done by bees and other insects. So, a fully formed, marketable strawberry is the result of autogamy (self-pollination) and allogamy (cross-fertilization) where insects are the vectors. But insects do much more to a strawberry than just pollinate it.

Fertilised achenes produce auxins and gibberellic acids, plant hormones that stimulate growth and thus are responsible for increasing the fruit’s size and weight. But these hormones also slow down the process of tissue-softening, so the fruit is firm for longer. This delay increases shelf life, which is hugely important for strawberry commercialisation: more than 90% of the harvested fruits can become non-marketable after four days in storage because of excessive softness, which induces fungal infections and mechanical injuries (Klatt et al., 2014). About one-third of the global food produced for human consumption is wasted during handling, transport and storage (Gustavsson et al., 2011); by increasing the number of pollinated achenes, insects do their bit to reduce these losses.

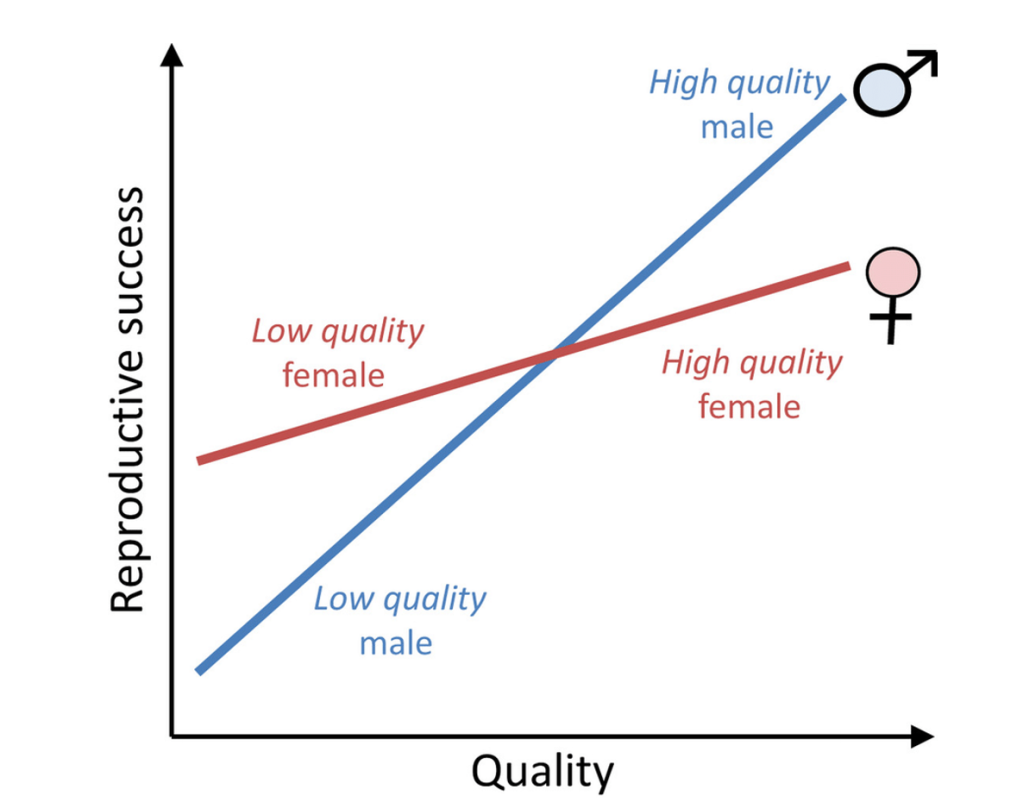

There’s a considerable range of strawberry varieties grown under different agronomic practices, but overall, Gudowska et al. (2024) estimated that insects contribute to 25% of fruit weight, a benefit worth US$ 5.4 billion per year to the producers worldwide. This ecological service is often attributed to the European honey bee (Apis mellifera), but bumble bees, honey bee-mimicking drone flies (Eristalis spp.) and the green bottle fly (Lucilia sericata) are among the most efficient pollinators of strawberry. And some other visitors could be even better: in Canada, MacInnis & Forrest (2019) observed that flower visitation by Augochlorella spp. and Lasioglossum spp. sweat bees resulted in fruits ~40% heavier when compared to flowers visited by honey bees. Here, insect sizes made all the difference: the relatively small sweat bees (5–7 mm in length) forage for pollen and nectar without disturbing the anthers, whereas the larger honey bees (>10 mm), which are after nectar only, often bend the anthers towards the stigmas. By doing so, honey bees may accidentally promote self-pollination, which may reduce fruit set when compared to cross pollination.

The garden strawberry is a case study of the role of pollination for crop production. It’s not an indispensable service in most cases, but without it, yields, produce quality and revenue can suffer significantly. A bowl of strawberries would not be as tasty, visually appealing or affordable without insects.