By Athayde Tonhasca

The Capayán ruins in Argentina’s La Rioja province are the remnants of a settlement from the colonial period in the late 17th century. This historic site has resisted the ravages of time and weather – the region is very dry – but is threatened by a seemingly harmless resident: the bee Centris muralis.

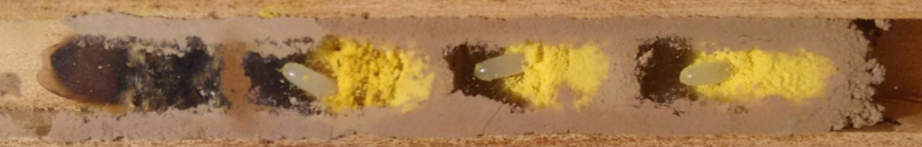

This solitary bee is endemic to Argentina, and like other species of the genus Centris, is common in deserts and arid areas, and active when other bees hide from the heat. Some Centris bees are known as ‘digger bees’ because they build their nests in the soil, sometimes in barren patches with no vegetation. So the soft, dry adobe walls in the Capayánruins turned out to be excellent nesting sites for C. muralis – muralis, by the way, meaning ‘of walls’ in Latin.

The bee’s choice of residence doesn’t bode well for the Capayán archaeological site. Initially, a C. muralis female makes small holes in a wall, which are used by other females to get in and construct their own nests, each comprising several brood cells. With time, the number of cells reach densities of around 700/m2, which is way too high for the fragile structure. Ad in the erosive power of rain that seeps into the holes created by bees, and the walls slowly crumble away; some parts collapse. One particular wall lost over 700 kg of building material and its thickness was reduced by 7 cm thanks to the relentless work of C. muralis.

Moving a long way north in the Americas, some home owners have their sights on carpenter bees (genus Xylocopa), which excavate holes in wood to build their nests. Any weathered wood will do, including man-made structures such as eaves, rafters, fascia boards, siding walls, decks and outdoor furniture. The effect of their excavations is mostly cosmetic, but significant structural damage can occur when the same area of wood is infested year after year. Carpenter bee holes also increase rot and decay. Persistent concentrations of carpenter bees may require home owners to control their numbers.

On this side of the Atlantic, the Davies’ colletes (Colletes daviesanus) and the red mason bee (Osmia bicornis)nest in holes and crevices, including in walls and mortar joints, sometimes in large numbers. These gatherings have prompted many a home owner to contract someone to get rid of bees that supposedly threaten building structures.

Lack of information and misinformation are opportunities for easy money; remedies and fixes can always be bought, even when they are not the most appropriate or none are needed. So it is helpful – and cheaper – to know that these bees are hardly worth the bother. The red mason bee nests only in pre-existing cavities, while the Davies’ colletes can tunnel into soft mortar, especially in old walls. However, their excavating is limited to soft materials such as sandstone and lime mortars already weakened by age and weathering – which may need repairing anyway. A watchful owner can discourage extensive, repetitive burrowing by raking out the affected mortar and repairing the joints (repointing) with new mortar made with cement. Insecticides are not a good idea: they have limited effectiveness and may stain masonry. These are recommendations from The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings and English Heritage, which one would expect to take seriously any possible risk to historically important edifices.

Also, we can’t overlook the environmental roles of these bees. Centris muralis is an important pollinator in arid and semiarid habitats, where not many insects find an easy living. Carpenter bees are skilled at buzz pollination, i.e., extracting pollen by vibrating their flight muscles, so they are excellent pollinators of tomatoes, aubergines, and other vegetables and flowers with hidden pollen. The Davies’ colletes is a widespread pollinator of wild flowers, especially daisy-related species (family Asteraceae), while the red mason bee pollinates a wide range of plants, including several fruit trees.

The perceived threats from these building dwellers are a good example of conservation conflicts: clashes between nature and human interests. But like any other conflict, there is ample room for compromise, which starts by understanding and assessing the problem. Centris muralis is causing damage in an unusual setting, and perhaps no mitigation is possible. But the risks posed by the other digger bees are not great or can be alleviated. Judicious evaluations, a degree of tolerance and a gentle touch would prevent us from compounding the stress inflicted upon pollinators by our over-dominance of the planet.