By Athayde Tonhasca

Charles II (1630-1685), king of England, Scotland and Ireland, had a reputation for benevolence and learning – the Royal Society came to be thanks to his auspices. But the good king wasn’t happy at all about the gossiping trickling from coffeehouses. Londoners from all walks of life would get together in one of the city’s dozens of coffee establishments to socialise, enjoy their pipes, comment on the news and, alarmingly, discuss theology, social mores, politics and republicanism. The king, anxious about potentially seditious blabber, issued a proclamation in 1672 aiming to ‘Restrain the Spreading of False news, and Licentious Talking of Matters of State and, Government’ because some folk ‘assumed to themselves a liberty, not only in Coffee-houses, but in other Places and Meetings, both publick and private, to censure and defame the proceedings of State, by speaking evil of things they understand not, and endeavouring to create and nourish an universal Jealousie and Dissatisfaction in the minds of all his Majesties good subjects.’

Nobody paid much attention to the king’s gripe, so two years later he came down hard on the miscreants with another proclamation: merchants were forbidden to sell ‘any Coffee, Chocolet, Sherbett or Tea, as they will answer the contrary at their utmost perils.’ But Charles had underestimated how much his subjects cherished their coffee: the proclamation triggered a huge outcry, and there were signs of public disobedience. Perhaps thinking of his father, who lost his head (literally) for being inflexible, the king quickly backpedalled. The proclamation was abolished within two weeks, and Londoners could go back to their chatting, reading, and sipping strong, bitter coffee.

Coffee made its way to Europe from Turkey in the mid-1600s, and the new drink quickly became popular and fashionable. The first British coffeehouse was opened in Oxford in 1652, and soon others popped up all over the realm. No alcohol was served, so sober and caffeine-boosted patrons could exchange and debate ideas or do business: Lloyd’s of London and The London Stock Exchange trace their origins to coffeehouses. In Oxford, they became known as penny universities: for one penny, the cost of a cup of coffee (the admission fee), any man – women’s presence was not encouraged – could rub shoulders with learned patrons and find out the latest on science, literature and philosophy. John Dryden, Isaac Newton, Samuel Pepys, Alexander Pope and Christopher Wren were some of the famous coffeehouse fans.

Eventually, as the British empire expanded through the East India Company‘s endeavours from 1720 onwards, tea became the country’s most popular hot beverage. Coffee began to make its way back to the top position in the late 1990s and early 2000s, helped in part by the arrival of mass-market coffee chains. Britain is not alone: coffee has become one the most popular drinks around the world, and consumption is increasing.

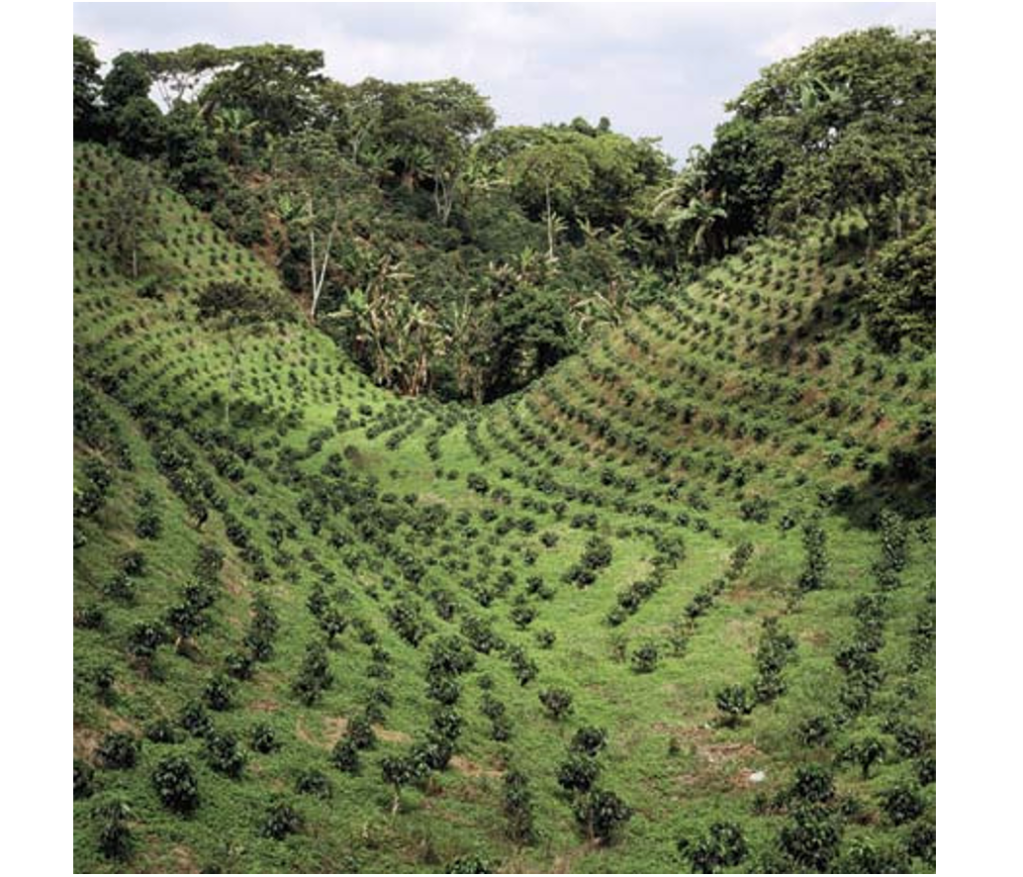

The expanding coffee market is good news to millions of small farmers and land holders in about 80 countries, who supply the bulk of the internationally traded coffee. Brazil accounts for ~40% of the global trade, followed by Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia and Ethiopia. Coffee is the most valuable crop in the tropics and a significant contributor to the economies of developing countries in the Americas, Africa and Asia. Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica) makes up 75-80% of the world’s production, and the remainder comes mostly from Robusta coffee (C. canephora), which is easier to cultivate than Arabica but produces an inferior beverage.

Arabica coffee has long been understood to be an autogamous plant, that is, it fertilises itself. This reproductive mechanism has the obvious advantage of doing away with pollinating agents such as insects. On the other hand, self-fertilising plants lose out on genetic diversity, so that they are more susceptible to unpleasant surprises such as novel pathogens. And autogamy does not guarantee fertilisation for species as finicky as C. arabica. Plants bloom a few times during the season, but flowers come out all at once and don’t stick around: they wither and drop off in 2-3 days. And if it’s too hot, too cold, too dry or too wet, flowers don’t even open. A coffee plant produces 10,000 to 50,000 flowers every time it blooms, but almost 90% of them fall without being fertilised. So, Arabica coffee bushes could use a little help with their pollination.

It turns out that the autogamous label is not quite correct for Arabica coffee. A growing body of observations and research have shown that fruit size and overall yield increase when flowers are visited by insects, especially bees. The proportion of well-formed, uniform berries also increases, resulting in a better-quality beverage. These results demonstrate that Arabica coffee relies on a mixed mating system: some flowers are self-fertilised, others are cross-fertilised by insects. And the figures support this view. On average, insect pollination increases fruit set by about 18%. The naturalised European honey bee (Apis mellifera) is one of the most important contributors to this service, but several other native bees visit coffee flowers, attracted to their abundant nectar and pollen.

There could be more to the pollination of Arabia coffee than the abundance of bees. Some studies suggest that having lots of bee species around also helps, possibly because a range of pollinators provide greater temporal and spatial flower coverage, thus reducing the chances of a receptive flower going without pollen transfer. If it’s proven to be the case that bee diversity makes a difference (the jury’s still out), the conservation of forest remnants that typically border coffee fields would be a judicious crop management practice, as they are home for many native bees.

When you are in the queue for your over-priced double espresso, long macchiato or cortado, you may have a negative thought about greedy coffee barons. In fact, for a £2.30 cup of coffee, the retailer keeps £1.70; five pence (~2%) goes to the grower. Fairtrade estimates that 125 million people depend on coffee for their livelihoods, but many of these small growers can barely scrape a living (World Economic Forum). Boosting productivity is one sure way of increasing farmers’ income, and here bees have much to contribute. Higher productivity also reduces the pressure on natural habitats, as coffee is often planted in areas previously occupied by native forests.

The Arabica coffee story exemplifies the reach of pollination services. The income of small farmers, revenues of developing countries, the conservation of tropical forests and related matters such as carbon storage and global temperatures, let alone your morning caffeine kick, are all linked in different degrees of relevance to the diligence of bees, some of them poorly known. Keep that in mind while you enjoy your next cup of coffee.