By Athayde Tonhasca

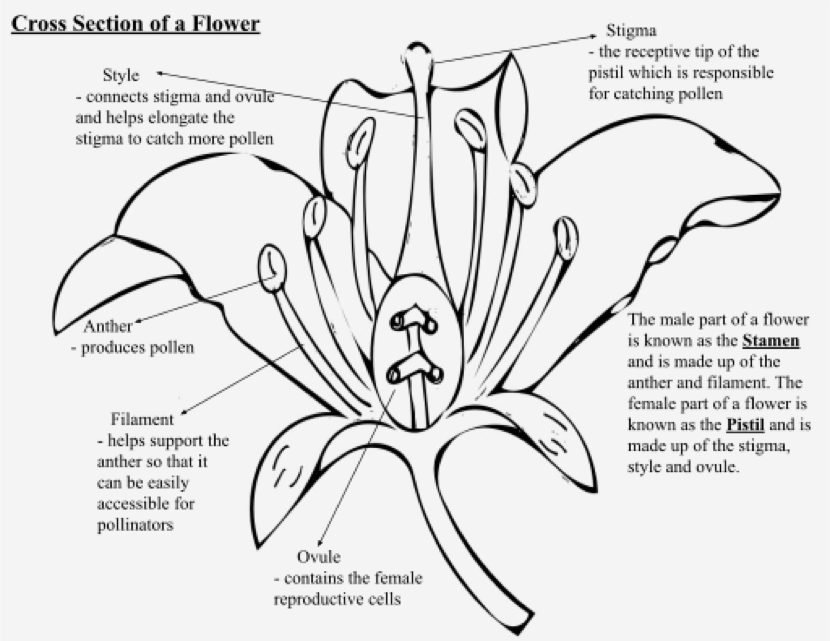

For most species of flowering plants, fertilization depends on the transfer of pollen from the male anthers of one flower to the female stigma of another.

For the majority of those flowers, pollen is released through the splitting open (dehiscence is the technical term for it) of mature anthers. But for approximately 6% of the world’s flowering plants, pollen is kept locked inside non-dehiscent anthers and accessed only through small openings – pores or slits – in their extremities. We refer to them as poricidal anthers.

Sometimes the whole flower has a poricidal arrangement, as it is the case for the tomato and related plants (Solanum spp.). Pollen is concealed inside a cone-shaped cluster of fused stamens and can only be released though a pore at the tip. Botanist say these flowers have a solanoid shape, after the name of the plant genus.

Extracting pollen from poricidal structures is not easy, but some bees know a way to do it.

A bee lands on one of these flowers, bites an anther and curls her body around it. She then let out bursts of fast contractions and relaxation of her thoracic muscles – those used for flying, but here the wings don’t move. This produces cyclical deformations of her thorax that last from fractions of a second to a few seconds, and can be repeated many times (think of a body builder flexing his pectoral muscles really, really fast). These movements generate vibrations that are transmitted to the anther, causing pollen grains to fall though the apical pores and land on the bee’s body, perhaps aided by electrostatic forces. Watch the whole sequence of events here and here.

This fancy pollen-harvesting manoeuvre creates a high-pitched buzz, hence it is known as ‘buzz pollination’; or as ‘sonication’ in technical reports. A physicist or an engineer could point out that this mechanism is not strictly sonication because it’s not sound that agitates and extracts pollen (such as in this example), rather direct vibrations on the flower. But ‘sonication’ is the term commonly adopted, so we will keep it. Bumble bees (Bombus spp.), carpenter bees (Xylocopa spp.), and some other bees can buzz pollinate: honey bees (Apis spp.) and most leafcutter bees (Megachile spp.) cannot. And apparently only females know the trick; males have never been recorded buzz pollinating.

Plant species with poricidal floral morphology are distributed across at least 80 angiosperm families, which suggests that buzz pollination has evolved independently many times. This has probably been helped by bees’ readiness to buzz for other reasons such as warning potential enemies, compacting nest materials, or cooling/warming their nest with wing beats.

Buzz-pollination syndrome, the name given for this plant-bee association, is not just a biological curiosity. It makes a huge difference for crops such as tomatoes, raspberries, cranberries, blueberries, aubergines, kiwis and chili peppers. These plants don’t necessarily need buzz pollination to reproduce, but they produce more and better fruit if they are buzzed because more pollen is transferred and more ovules are fertilised.

In the late 1980’s, Belgian and Dutch companies developed techniques to rear on a large scale the buff-tailed bumblebee (Bombus terrestris), the ultimate buzz pollinator. Local producers of greenhouse tomatoes began replacing costly mechanical pollinators with boxes containing bumble bee hives, and a global, multi-million pound industry was born. Today, every tomato bought in a European supermarket has matured with the help of a commercially reared bumble bee.

We may see pollination as a harmonious relationship where plant and insect go out of their way to help each other, but this is mistakenly romantic. A bee aims to take all the flower’s pollen: pollination happens because a few grains are dropped or rubbed off by accident. And a plant produces as little nectar and pollen as necessary to entice a flower visit. So the association between pollinators and flowers is best described as a mutual exploitation. Buzz pollination fits nicely into this scenario. Poricidal anthers prevent excessive pollen expenditure by rewarding only buzz-pollination specialists, which increases the chances of pollination. Plants with poricidal structures typically secrete little or no nectar but their pollen is rich in protein, which convinces a bee to go to the trouble of buzzing to gain a small dose of the yellow stuff. It’s a clever, efficient trade agreement in the pollinator’s world.