By Athayde Tonhasca

‘Picture to yourself everlasting bleak sand dunes with no buildings. Only rabbits find a little nourishment here; they eat a substance which quite unjustifiably goes by the name of grass. It is a sand desert where the wind always blows often howls filling the ears with sand. Between us and America, there is nothing but water a sea whose mighty waves are always raging and foaming. Now you will have some idea of the place where I am living. Without work the place would be intolerable.’

Thus Alfred Nobel (1833-1896) – of Nobel Prize fame – described to his brother the Ardeer peninsula, the Scottish site chosen to host his British Dynamite Company in 1871. The Scottish tourism board might have looked askance at Nobel’s verdict, but Ardeer was the ideal place for the manufacture of temperamental products such as dynamite and gelignite (blasting gelatine). The peninsula was relatively isolated from skittish neighbours, yet fairly close to Glasgow ports. As a bonus, the site was covered with dunes, which were an abundant source of building material for blast walls that protected life and property against accidental explosions.

By 1902, Nobel’s explosives factory was the largest in the world. Manufacture shifted to other products after the plant became part of Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) in 1926, but production started to dwindle. By the 1980s, most operations ceased: Ardeer train station, the dining hall, engine houses, boilers, warehouses and countless other buildings were abandoned: a large portion of the Ardeer Peninsula had become derelict.

Today, a visitor to the once mighty Nobel Enterprises site will find crumbling sheds covered by graffiti and half swallowed by the sand, tracks of weedy tarmac, rusty pipes and barbed wire, and pieces of broken equipment scattered everywhere. Such a place definitely would not qualify as a beauty spot. But these eerie remnants have a significant ecological value.

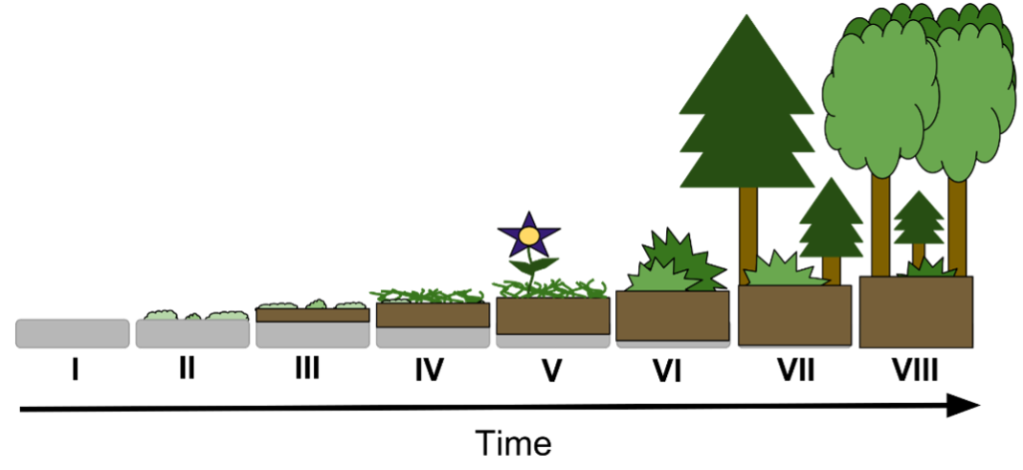

Land that has been previously built on or developed such as the Nobel factory is classed as a brownfield site – as opposed to greenfield sites, which are land that has never been developed. Some brownfield sites are inhospitable places, layered with tarmac or concrete, and often contaminated with toxic chemicals. But many of these areas are not hazardous; quite the opposite. They are usually populated by patchy, thin vegetation (sometimes because of poor soils and lack of water) comprising weeds, grass and scrub; the landscape is a mixture of bare ground, temporary pools, scattered logs, stones or rubble. These post-industrial sites, old quarries, disused open mines, spoil heaps, gravel pits, and other abandoned enterprises may look like the settings of a Mad Max film, but they are great opportunities for pioneer species – those first to colonize a newly created environment. Ecologically, open ground areas function as habitats in the initial stages of succession – that is, on the way to becoming closed-canopy forests.

Many species benefit enormously from these semi-open spaces that are not yet taken over by strong, dominant competitors. Pollinating insects in particular have at their disposal sunny spots for basking, a variety of wildflowers for nectar- and pollen-feeding, patches of bare ground for nesting, and some solid, sheltered structure such a pile of rubble for hibernation. They have it all. Even better, these sites are mostly free from human interference – people tend to avoid them. Evolving brownfield sites have their own special name: open mosaic habitats. They are sufficiently valuable to biodiversity to be considered a category of UK priority habitats.

Ardeer is an exemplar evidence of the value of open mosaic habitats. It harbours the most diverse assemblage of bees and wasps in Scotland: 113 species, including many scarce ones such as the northern colletes (Colletes floralis) and the coastal leafcutter bee (Megachile maritima). Beetles, moths and butterflies are also richly represented (Philip et al., 2020).

By their very nature as successional habitats, brownfields are ephemeral; in 15-20 years, they are likely to be overtaken by scrub and eventually become woodland. They may not even last that long, as they are prime targets for makeovers; Ardeer itself is being considered to become a housing development, a golf course, a marina, a wind farm, or even a site for a nuclear fusion reactor. The limited aesthetic appeal of brownfields induces few objections to their re-development. But considering their value for biodiversity, their keeping and management to retain their successional nature are equally valid options for their future.