By Athayde Tonhasca

Philip Miller (1691-1771), author of the renowned The Gardeners Dictionary and Fellow of the Royal Society, was a keen experimenter in plant propagation. In a 1715 letter to a friend, Miller described his observations of bees visiting tulip flowers, “which persuades him that the Farina may be carried from Place to Place by Insects” – Farina is the Farina Fecundens (fertilizing flour), or pollen, which fellow naturalists suspected played an important part in plant reproduction. Meanwhile in America, Arthur Dobbs (1689-1765), Governor of North Carolina, promoter of expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage and amateur scientist, came to a similar conclusion: “I think that Providence has appointed the Bee to be very instrumental in promoting the Increase of Vegetables”.

Philip Miller and Arthur Dobbs were two of the pioneer naturalists who recognised and assessed the role of insects in plant reproduction. We learned a great deal since then, so that today plant-pollinator associations are considered some of the best examples of mutualisms, that is, relationships between two species that benefit both. ‘Mutualism’ invokes noble concepts such as cooperation, teamwork, union, and common good; so, analogies with human behaviour were just too tempting. The anarchist Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921) cited examples of mutualism in the natural world as arguments against ruthless competition in human societies, while ecologist Warder Clyde Allee (1885-1955) and colleagues, in their influential Principles of Animal Ecology, made numerous references to human cooperation in discussions about mutualism (Boucher et al., 1982). These comparisons with human values risk distorting the true character of mutualism in the natural world, as is the case with pollination. There’s little collaboration here: plants give away as little pollen and nectar as possible because these products are metabolically expensive; sometimes they cheat, giving no reward at all to flower visitors. Pollinators on the other hand would take as much resource as possible, with no altruistic regard for plants’ needs. Instead of cooperation, this type of relationship is best described as mutual exploitation (Westerkamp, 1996). Or, as Danforth et al. (2019) put it, ‘pollinators are like an overly demanding lover – they are great to have around at times, but if left without boundaries, they can take over your life and ruin it.’

Plants are in a delicate position: they need to attract insects to transfer their pollen but must be parsimonious in their rewards, otherwise these will be quickly depleted. To sort out this dilemma, many species evolved a range of adaptations to regulate access to pollen and nectar, and to discourage floral robbers (consumers that do not pollinate). Some plants exclude unsuitable visitors by restricting their pollen to specialised buzz pollinators; others rely on explosive pollen release, while some take the route of morphological tinkering such as keel flowers.

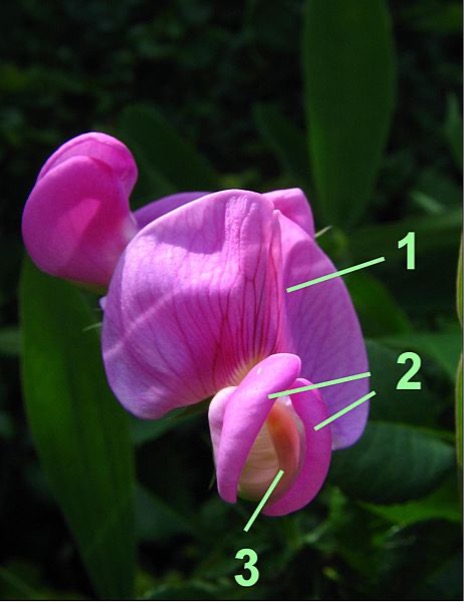

Keel flowers have five petals: a large one on top called the banner (also known as the vexillum or standard petal), two concave ones on the sides (the lateral wings or alae), and two at the base: these are stuck together to form the keel, which encloses the reproductive organs.

Keel flowers are common in the subfamily Papilionoideae (or Faboideae) of the legume family (Fabaceae). They are also known as papilionate flowers, from their resemblance to butterflies – papilio in Latin. Papilionoideae comprises an estimated 14,000 species, or over 70% of all legumes. They are found in a range of habitats, and many of them are important sources of human and animal food, such as soybean (Glycine max), beans (Phaseolus spp.), clovers (Trifoliumspp.) alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and peanut (Arachis hypogaea).

The ungainly shapes of keel flowers seem to have been designed to make life a bit difficult for pollinators. Not to put them off completely – that would be suicidal – but to make them work hard for their reward. To access the nectar, a visitor must grab the flower, push the keel down, while simultaneously prising apart the lateral wings, engaging their legs and mouth in elaborate contortions. These manoeuvres expose the stigma (female parts) and the anthers (male parts), which touch the visitor and ensure pollen transfer.

These operations require strength and technique; visitors that do not have the physical apparatus or sufficient power such as butterflies and flies are mostly excluded from keel flowers. Hummingbirds and other birds are also barred, as they can’t open the petals with their beaks and the keels are not big enough for landing (Westerkamp, 1997). Only bees, and only the larger ones at that, can deal with the challenge. Watch bumble bees expertly working their way around lupin (Lupinus sp.) flowers, and note the spike-like structure – the keel – poking out between the lateral wings as bees push them apart. On touching the keel, bees are dusted with pollen. And here, a leafcutter bee (family Megachilidae) illustrates the labour required to get the nectar in a brown hemp flower.

Keel flowers block the less desirable visitors, saving pollen and nectar for the reliable larger bees. It’s not surprising then that so many plant species have adopted this aesthetically peculiar but highly effective flower shape.